Category: 'Practice Notes'

November 30th, 2011 · Comments Off on When during the year does the Texas Supreme Court issue the bulk of its opinions?

It’s been nearly three months since the start of the Texas Supreme Court’s fiscal-year term. How are things going at the one-quarter mark?

As of Monday morning, there were just two signed decisions this Term. With the opinions released Monday afternoon for Allcat, there are now three — and the Term’s first separate opinion. Along the way, there have also been five per curiam decisions. (The click-through table is on DocketDB.)

A slow start was to be expected, given the small number of cases carried forward this Term. (( Only one of those has been decided: Sharyland Water Supply Corporation v. City of Alton, et al., No. 09-0223. ))

But the conventional wisdom is that the Court always has a slow start in the fall (the first quarter), as it absorbs new law clerks. Similarly, the conventional wisdom suggests that the summer (the fourth quarter) is the busiest for opinions, as the Court tries to clear the decks before the end of the fiscal year.

Do the numbers bear this out?

I took a look at the last five years of opinions, distinguishing between signed opinions and per curiam opinions. I figured out what percentage of each year’s opinions fell into each fiscal “quarter” — 1Q (September to November), 2Q (December to February), 3Q (March to May), and 4Q (June to August). The table below represents the average of those years. (( Yes, it’s just five years. Appellate geeks — like sports nuts — often trade in sample sizes far too small to be “significant.” ))

| |

Q1 |

Q2 |

Q3 |

Q4 |

| Signed Opinions |

10% |

21% |

30% |

39% |

| Per Curiams |

20% |

26% |

27% |

27% |

As expected, the signed opinions increase as you progress through the quarters: roughly 10%, 20%, 30%, and 40%. By contrast, the per curiams show a slight dip in the first quarter and then are split almost evenly among the remaining three quarters.

Why the difference here?

The per curiams show a dip in the first quarter and then are fairly steady for the rest of the Term. That seems to bear out the idea that it takes a little time to get new law clerks up to speed.

Why do signed opinions show a much more pronounced pattern? One answer might be that signed opinions tend to follow argued cases and are thus dependent on the Court’s highly seasonal argument scheduling. (In recent years, arguments have been scheduled from September through March or April.)

Less obviously, the two types of decisions have different effects on the Court’s statistics if carried forward from one Term to the next. Signed opinions tend to show up as “causes” and thus are highlighted when they linger. By contrast, per curiam opinions usually result from petitions granted only at the moment the opinion issue issued — and that, before that time, were just part of the general petition pool. With those incentives, it is not too surprising if the Court prioritizes signed opinions as the summer winds to a close.

Tags: Practice Notes

November 17th, 2011 · 3 Comments

Our speaker at today’s Austin Bar Civil Appellate Lunch was Robert Dubose, whose topic was “Can I Cite Wikipedia? The Ethics of Citing Online Information on Appeal.”

This blog post shares a tip for how to cite Wikipedia, when you’ve already decided that you want to refer to the largest single compendium of human knowledge ever assembled.

Accuracy vs. Authority

Robert pointed out that Wikipedia tends to be very accurate, at least for topics that get a relatively high volume of community involvement. Studies show that it can be more accurate that a carefully peer-edited encyclopedia. On the other hand, the prose tends to be choppy and difficult to read in large doses — it’s a patchwork of styles from different contributors. So you probably don’t want to read the history of a major event (like World War II) on Wikipedia, even if there are a huge number of (accurate) facts.

When you think about writing a formal citation to Wikipedia, you confront the difference between authority and accuracy. It’s certainly not authoritative based on the identity of any particular author — you do not know who wrote an article, nor do you know who has contributed edits (or approved of the text and left well enough alone). But the fact that so many people have an editing pen creates a kind of distributed peer review. As Clay Shirky put it: “[Wikipedia] took one of the best ideas of the last 500 years — peer review — and expanded its field of operation so dramatically that it changed the way authority is configured.”

For a profession in the authority business — in how we cite cases, in how we pitch our own skills, in how we deal with expert witnesses — this disconnect can be hard to accept. But a crowdsourced reference can be extremely valuable as a place to start deeper research or for information more generally known.

When You Do Cite Wikipedia, How Should You Do It?

Let’s say you want to cite Wikipedia for a fact about the world. How do courts do it? Is there a better way?

The Beaumont Court of Appeals cited Wikipedia in a 2009 decision, In re K.E.L., No. 09-08-00014-CV (Tex. App. — Beaumont Feb. 26, 2009). Here’s footnote 3:

“MySpace is a social networking website with an interactive, user-submitted network of friends, personal profiles, blogs, groups, photos, music, and videos for teenagers and adults internationally.” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, MySpace, at http:// en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MySpace (last visited Feb. 3, 2009).

The Court chose this URL:

http:// en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MySpace

As has become standard for internet citations, it used the parenthetical “last visited Feb. 3, 2009.” Is that really helpful? For most websites, can you do anything at all with a “last visited” date?

If you follow the court’s link, you get the most current version of the article. On the current version as it appears today, the sentence quoted by the Texas court of appeals now reads: “Myspace is a social networking service owned by Specific Media LLC and pop star Justin Timberlake.” That’s an entirely different emphasis than it had in 2009. Indeed, there’s now a prominent section titled “Decline: 2008 – present,” explaining how it lost the social-networking wars to Facebook. In a few more years, the continually edited entry may look more like the GeoCities entry today. (“Yahoo! GeoCities is a web hosting service, currently available only in Japan.”)

It’s Not Impermanence. It’s Version Control.

That brings up a criticism you hear about Wikipedia: You shouldn’t cite it because it changes all the time, and you don’t know what your reader will see.

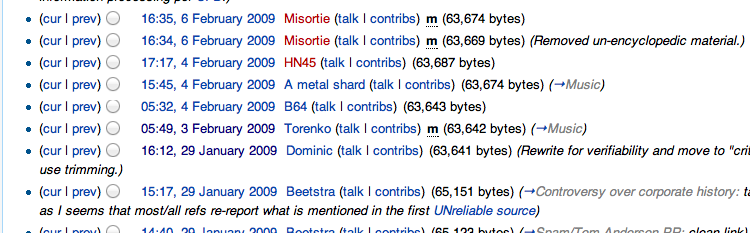

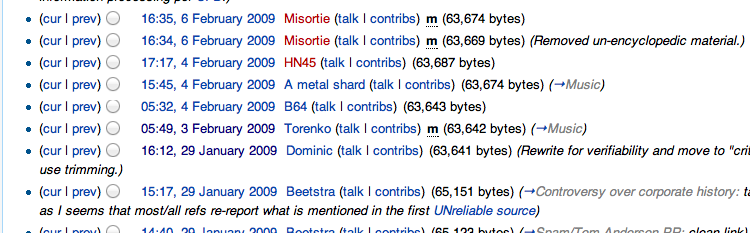

But with Wikipedia, as many of you know, there is a revision history. You can browse an article’s edits with its “View History” tab, right next to the search box in the top right.

This shows you a list of each edit, complete with the user name (or IP address) of the person who submitted each edit.

If you look back about 630 edits into the list, there’s a version from 5:49 AM on February 3, 2009. Some edits fall in the middle of the day, and other times the article is edited several times in one day. But we got lucky with this one. The “last visited” date might actually point us to the right place.

You Can Cite To a Permalink to Today’s Version

If you followed the links that I embedded above, you did see precisely the pages I wanted you to see — the older version from a specific moment in 2009, and the snapshot that appears right now as I’m writing this post. You can check back next week or next year, and you should see the same text.

Wikipedia uses the term “permalink” to describe this type of URL. The permalink to the current version (the one you’re citing) is listed in the left-hand column under the Toolbox menu. Click the word “Permalink” in that list, and the page reloads as itself to what your reader will see. You can then grab the URL and paste it into a brief.

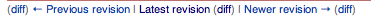

You’ll notice a pink status bar when you load a page by its permalink. It tells you whether or not you are viewing the most current version. It also gives you the option to generate a diff between the link you followed and the current version — a very quick way for a reader to confirm whether the facts have changed in the intervening time. If you click on this “diff”:

You get this:

As lawyers, we should be drooling with envy. We all know what needs this type of easy-to-link version control that lets the reader easily determine what has changed over time: statutes.

Legal citations for amended statutes devolve into the kind of soup seen in footnote 2 of this same opinion: “Although the Legislature amended certain aspects of the statute that provides the terms for standard possession orders after the possession order at issue here, the changes are not pertinent to this appeal. Therefore, we cite the current version. Compare Tex. Fam. Code Ann. § 153.312 (Vernon 2008) with Act of May 27, 2007, 80th Leg., R.S., ch. 1041, § 2, sec. 153.312(a), 2007 Tex. Gen. Laws 3594, 3595 (current version at Tex. Fam. Code Ann. § 153.312(a) (Vernon 2008)), and Act of May 29, 2005, 79th Leg., R.S., ch. 916, § 12, sec. 153.312(b), 2005 Tex. Gen. Laws 3148, 3151-52 (current version at Tex. Fam. Code Ann. § 153.312(b) (Vernon 2008)).)”

Permalinks are Better Than “Last Visited.”

This is what the permalink URL looks like for the February 3, 2009 version of the MySpace wikipedia page:

http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Myspace&oldid=268197951.

When you are citing Wikipedia, you should be using a permalink URL that looks like that.

Last year, I was critical of the new Bluebook for how it treats URLs as if they were the names of volumes of books rather than pinpoints to specific pages. The emphasis seems to be on what the researcher did (i.e., “last visited” or “downloaded from”) rather than how the next researcher can quickly get to the right resource. As I wrote:

URLs are ugly in print, but they are “uniform resource locators.” They are built to do this job with precision. And an ugly citation that works is far superior to a pretty one that doesn’t.

When a site like Wikipedia gives you the gift of precise, persistent URLs, you owe it to your readers to take advantage of them. (( As a practical matter, you should also take a screenshot or make a good printout for your own records. On the Mac, I’m a fan of the program LittleSnapper, which lets you take an image of an entire webpage, including below the fold [1MB file]. The software is marketed to web designers, but it’s handy for archivists, too. ))

Tags: Legal Writing · Practice Notes

September 2nd, 2011 · 2 Comments

This spring, the Texas Legislature made it easier to get appellate review early in a case. (( The new language of Texas Civil Practice & Remedies Code §51.014:

(d) On a party’s motion or on its own initiative, a trial court in a civil action may, by written order, permit an appeal from an order that is not otherwise appealable if:

(1) the order to be appealed involves a controlling question of law as to which there is a substantial ground for difference of opinion; and

(2) an immediate appeal from the order may materially advance the ultimate termination of the litigation .

…

(f) An appellate court may accept an appeal permitted by Subsection (d) if the appealing party, not later than the 15th day after the date the trial court signs the order to be appealed, files in the court of appeals having appellate jurisdiction over the action an application for interlocutory appeal explaining why an appeal is warranted under Subsection (d). If the court of appeals accepts the appeal, the appeal is governed by the procedures in the Texas Rules of Appellate Procedure for pursuing an accelerated appeal. The date the court of appeals enters the order accepting the appeal starts the time applicable to filing the notice of appeal. )) These permissive interlocutory appeals require convincing both the trial court and the court of appeals that a particular key issue should be given immediate appellate review to remove any uncertainty before the trial moves forward.

The Texas Supreme Court has now amended the trial and appellate rules of procedure (PDF) to conform to that statute.

The new rules provide that:

- When the trial court thinks an order appropriate for this kind of early interlocutory review, it should say so in the order itself (or an amendment of that order). Tex. R. Civ. P. 168.

-

The parties then have 15 days to file a petition with the court of appeals, including some basic elements of a brief (required tables and a statement of facts), as well as an argument focused on the statutory requirements: “why the order to be appealed involves a controlling question of law as to which there is a substantial ground for difference of opinion and how an immediate appeal from the order may materially advance the ultimate termination of the litigation.” Tex. R. App. P. 28.2(e). The petition can be no more than 15 pages. Tex. R. App. P. 28.2(g).

-

The court of appeals can grant the parties an extension of time to file this petition. Tex. R. App. P. 28.2(d).

-

A response would be due within 10 days, with any further reply within 7 days. Tex. R. App. P. 28.2(f).

-

The court of appeals will generally decide whether to take the petition without oral argument and “no earlier than 10 days after the petition is filed” (giving the appellee a chance to respond). Tex. R. App. P. 28.2(j).

Is this like Texas Supreme Court petition practice?

The commentary published with the order says, “The petition procedure in Rule 28.2 is intended to be similar to the Rule 53 procedure governing petitions for review in the Supreme Court.” That is true as a matter of form, with the page limits and quick deadlines.

But the differences are also significant. While the Texas Supreme Court has broad discretion over which substantive issues it wants to hear at all, this rule is focused on timing — should the certified order be addressed now on permissive appeal, or should it wait for a later merits appeal? The question is not importance to the jurisprudence, but optimizing the efficiency of a single suit.

A more subtle difference is that, in the Texas Supreme Court, it is common for a respondent to simply waive filing a response until one is requested by the Court. These rules do not provide for that “waive and wait” process. If an appellee wants to oppose, they have ten days to file a response.

The more obvious comparison is with federal permissive interlocutory appeals under 28 U.S.C. 1292(b). Federal appellate courts do not always agree to take up these appeals, even after an order is certified by the trial court. It will be interesting to see which types of orders Texas trial courts agree to certify — and which the courts of appeals choose to decline.

Tags: Practice Notes

August 15th, 2011 · Comments Off on New SCOTX order: E-filing moves from voluntary to mandatory in one month

The Texas Supreme Court has been telling us that e-filing would move from “voluntary” to mandatory this fall. Now, the Court has set the date. Beginning September 12, 2011, all motions and briefs submitted by counsel (( The order carves out pro se litigants, who may use the e-filing system if they choose. )) must be sent through e-filing.

Like its previous e-brief orders, this one makes some fine-tuning adjustments to the process. The required paper copies are now due “within three business days after” e-filing, not the next business day. And the number of copies needed now varies by type of filing:

| Documents |

Paper copies |

| Motions |

No copies |

| Petitions, responses, and petition-stage replies |

2 copies |

| Amicus briefs |

2 copies |

| Briefs on the Merits |

4 copies |

| Record in original proceeding |

1 copy |

Advocates should note: The Court wants more paper copies of merits briefs than petitions. This difference, I am told, reflects the Justices’ preferences about when they would want a paper copy. More wanted access to a paper copy of merits briefs than petitions.

There are two other changes that affect paper copies.

First, the Court now specifies that the paper copy must be the file-stamped PDF returned to you by the e-filing system. The Court wants to ensure that the paper version matches the final e-filed version. (This also makes pretty clear that the e-filed version is the official one.)

Second, the Court now specifies which appendix items should be included on paper. According to the new order,

Unless voluminous or impracticable, the appendix to a paper copy need only include the content required by Texas Rules of Appellate Procedure 52.3(k) and 53.3(k).

This could affect the evolving conversation about whether to include just a few hyperlinks or whether to include as many hyperlinked authorities as possible. Under the old rules, embedding a document into your PDF meant that it also had to be printed and bound into the paper courtesy copies as well (and could have meant very large paper documents). The new rules give counsel more latitude. They “need only” include paper versions of the appendix items required by the rule.

This last change should let advocates focus on doing what makes the official electronic version as helpful as possible.

Here’s the full order: Electronic-Copy and Electronic-Filing Rules for the Supreme Court of Texas

Tags: Practice Notes

August 8th, 2011 · Comments Off on “Common Blunders in Texas Supreme Court Briefs”

Last Friday, Texas Lawyer published a helpful article: “Common Blunders in Texas Supreme Court Briefs”. It was written by Martha Lackritz, who just finished a two-year clerkship with Chief Justice Jefferson. She offers solid advice.

Most of her points are applicable to any appellate court. There are two points, however, that highlight an important difference in practicing in a state’s highest court.

[Read more →]

Tags: Legal Writing · News and Links · Practice Notes

July 22nd, 2011 · Comments Off on Fall oral argument calendar released [Jul. 22, 2011]

With today’s orders list, the Texas Supreme Court released its fall argument calendar through mid-November.

The Court also formally accepted the Fifth Circuit’s invitation to answer a certified question about whether an insurer must cover mental anguish claims under a business’s liability policy.

Oral Arguments

September 13, 2011

-

Thota: rescheduled for November 10, 2011

-

The Finance Commission of Texas, The Credit Union Commission of Texas, and Texas Bankers Association v. Valerie Norwood, et al., No. 10-0121

-

Basith Ghazali, M.D. v. Patricia Brown No. 10-0232

September 14, 2011

-

City of Austin v. Harry M. Whittington, et al., No. 10-0316: rescheduled for December 6, 2011

-

Texas Department of Public Safety v. Caruana, No. 10-0321

-

Texas Department of Insurance, Hon. Mike Geeslin, Danny Saenz v. American National Insurance Co. and Americpublic/docketan Life Insurance Co., No. 10-0374 (Justice Hecht not sitting)

September 15, 2011

-

Prarie View A&M University v. Diljit K. Chata, No. 10-0353

-

Atmos Energy Corporation, Centerpoint Energy Resources Corp. and Texas Gas Service Co., v. The Cities of Allen, et al., No. 10-0375

-

El Apple I, Ltd. v. Myriam Olivas, No. 10-0490

October 4, 2011

-

SafeShred, Inc. v. Louis Martinez, III, No. 10-0426

-

Shell Oil Company, et al. v. Ralph Ross, No. 10-0429

-

Weeks Marine, Inc. v. Maximino Garza, No. 10-0435

October 5, 2011

-

Natural Gas Pipeline Co. v. William Justiss, et al., No. 10-0451

-

Hearts Bluff Game Ranch, Inc. v. The State of Texas and the Texas Water Development Board, No. 10-0491

-

Matthew W. Wasserman, M.D. v. Christina Bergeron Gugel, No. 10-0513

October 6, 2011

-

Port Elevator-Brownsville, LLC v. Rogelio Casados and Rafaela Casados, No. 10-0523

-

In re United Scaffolding, Inc., No. 10-0526

-

Rusk State Hospital v. Dennis Black and Pam Black, No. 10-0548

November 8, 2011

-

Texas West Oaks Hospital, LP and Texas Hospital Holdings, LLC v. Frederick Williams, No. 10-0603

-

In re the Commitment of Michael Bohannan, No. 10-0605

-

Texas Electric Utility Construction, Ltd. v. Infrasource Underground Construction Services, LLC, No. 10-0628

November 9, 2011

-

Kerry Heckman, et al. v. Williamson County, et al., No. 10-0671

-

In re Frank Kent Motor Co. d/b/a Frank Kent Cadillac, No. 10-0687

-

Jack Edward Milner v. Vicki Ann Milner, No. 10-0776

November 10, 2011

-

Venkateswarlu Thota, M.D. and North Texas Cardiology Center v. Margaret Young, No. 09-0079 [Rescheduled from September 13, 2011]

-

In re XL Specialty Insurance Co. and Cambridge Integrated Services Group, Inc., No. 10-0960

-

Nicholas Traxler v. Entergy Gulf States, Inc., No. 10-0970

Tags: Order Lists · Practice Notes

As this post appears this morning, I’m standing up to speak at the Advanced Administrative Law Conference in Austin. (If you’re there, then hello!)

My talk is a Texas Supreme Court update, and here are my slides:

I cover some of the recent voting patterns, some recent docket trends that might affect administrative-law issues, and talk about a few cases pending on the docket.

If you are curious about the voting patterns, then get the slides while they’re fresh. The data is up-to-date through last Friday’s orders, but it could well be out of date tomorrow

Tags: Practice Notes

I will not be posting about the Friday orders list this week or next. You are on your own until June 22nd, when I return to the blog.

As blog readers know, the Texas state appellate courts are shifting toward electronic briefs. Unlike the federal system, the Texas rules permit advocates to make use of hyperlinks and encourage the use of internal bookmarks to ease navigation. The focus is on making the briefs more useful to the ultimate readers — the judges and law clerks who will use them to decide cases and write appellate opinions.

Last Thursday, I gave a presentation about electronic briefs with Blake Hawthorne at the UT Conference on State and Federal Appeals. We covered quite a bit of ground for a thirty-minute talk — the basics of how to make these briefs, some survey results from judges and staff members who have been using them for the past year, and some clips of video interviews with Texas Supreme Court Justices on the same subject.

See the video interviews and get the slide deck

Tags: Electronic Briefs · News and Links · Practice Notes