Category: 'Practice Notes'

October 9th, 2019 · Comments Off on When should we expect the cases argued in the fall to be decided?

The Court’s new schedule seems simple enough. Cases argued in one term are decided before that term formally ends on August 31. The Court now treats June 30 as a self-imposed deadline, roughly mirroring the schedule of the U.S. Supreme Court (and leaving time for a meaningful summer break in July).

As advocates, the great benefit of having this single, fixed point on the calendar is that we now have a non-shrug-emoji answer to every client’s question, “When will my argued case be decided?” We can now confidently say “by June 30” (or slightly less confidently, “by the Friday before June 30, unless for some reason your case is abated”).

For cases argued in March and April, that’s super helpful. The median time for cases to be decided last term was 15 weeks; there are barely that many weeks between mid-March and the end of June. There just isn’t much room for variance. It’s hard to be wrong.

But for cases argued in September, the same fixed June 30 deadline is a school year away. Is there more precision we can offer? Does having more time remaining in the year allow the timelines to expand? Does having a relatively clean plate at the beginning of a term (with no cases carried over) allow at least some justices to write more quickly to get a head start?

The answer, it turns out, is yes and yes. Cases argued in September and October show a wide variance in decision time. The three fastest decisions of last term were argued in September. So, too, was the slowest decision of the term.

Some new Time to Decision charts

The small size of this data — and the varying gravitational pull of the June 30 deadline at different times of year — makes me reluctant to present a single summary statistic. Instead, I put together a new kind of chart to illustrate what is going on. If you’ve read this far, it might be worth your time to look over these charts to get your own visual sense of the patterns.

On the Time to Decision chart, each argued case is displayed as a bar on the graph with the endpoints showing when during the year it was argued, when it was decided, and (implicitly) how long the decision took. You can hover your mouse over the bar to see exact dates. The rightmost column shows the authoring justice; multiple justices means there were separate opinions. The chart has buttons at the top that let you reorder things by argument date, decision date, or time to decide.

What’s striking is how different the 2019 term looks compared to the pattern just two years ago. In the 2016 term and 2017 term, the Court took a different approach to the same June 30 deadline. There was no burst of quick decisions early. Instead, the cases argued last were the ones decided most quickly, while the cases argued first took much longer to decide.

Something is different. A notable, visible change is that the Court has started to hold two argument sittings in each of September and January — its return from summer break and from the holiday break. The direct effect was to shift some arguments earlier in the term, leaving even more time before the deadline of June 30. Taken alone, this would allow decision times for those early cases to grow even longer. But what the data for 2019 shows is different. Cases argued in the September and January sittings were among the very fastest decisions.

This burst of fast decisions seems like the product of focused effort by the Court to finish some opinions quickly. Part of that might have been motivated by Justice Johnson’s scheduled retirement in the fall. But other justices also wrote quickly last fall, and I would not be surprised if this general pattern continues.

So, is there a more refined answer to the question of how long decisions argued in September and October will take? Based on last term’s data, the median time to decide all cases was 15 weeks after argument, with most cases taking between 10 and 21 weeks from argument. And based on these charts, you can get a sense of how the time in the year a case is argued affects how quickly it might be decided.

If all that’s too much, you can just tell folks “by June 30” and rest easy knowing that you are unlikely to be wrong. If a decision does come quickly after argument, you can always break out that shrug emoji then.

Tags: Practice Notes

June 1st, 2018 · Comments Off on Today’s grants and the shape of next year’s argument calendar [Jun. 1, 2018]

With the first orders list of summer, the Texas Supreme Court issued opinions in four cases, chose twelve new cases to be argued in the fall, and formally dismissed a mandamus petition that was (very briefly) set for oral argument this past March.

Next year’s argument calendar

At this week’s conference, the Court made grant-or-deny decisions about some of the pending fully-briefed petitions that had been studied by staff. The Court chose 12 to be argued this fall, and it denied review for 9 others. Other fully-briefed petitions remain pending (the blog tracks those, too), and I expect to see another round or two of “grants” later in the summer.

With this week’s additions, the total number of grants for next year now stands at 14, which could fill out the September argument sitting (even if no more grants were made).

What struck me, when I looked at next year’s calendar, is that the Court seems to be experimenting with front-loading arguments into September and January, leaving more calendar time for drafting of opinions.

-

-

Snapshot of the Sept. 2018 calendar

-

-

Snapshot of the Jan. 2019 calendar

For comparison, in recent years the Court has tended to only have one argument sitting in September (2017, 2016, 2015, 2014) and one in January (2018, 2017, 2016, 2015). The sole exception (Sept. 2015) had sittings in the first and last weeks of the month.

The Court hasn’t explained its thinking, but an educated guess is that shifting arguments earlier in the term could ease some of the internal scheduling issues created by having a single fixed June 30 “deadline” for getting opinions out the door. More time to deliberate, in more cases.

We may see other ripple effects of shifting arguments forward in the term. For example, there might be more time pressure to consider “grants” in November or December to fill out a January argument calendar. Or it’s very possible that some of these planned argument dates might, if not filled, quietly disappear as the Court updates its online calendar.

Today’s decisions

The Court issued opinions in four argued cases today, including one 5-4 decision.

There are now 18 argued cases remaining to be decided this term. (The blog tracks those cases here.)

Petitions chosen for oral argument

These are the 12 petitions chosen for future oral argument:

- Michael Joe Sorrell and Sorrell Family, Ltd Partners v. Estate of Benjamin Hardy Carlton, III, No. 16-0874

-

Thomas A. Lalonde, Jr., P.E.... v. Paul Gosnell and Kim Gosnell, No. 16-0966

-

RSL Funding, LLC and RSL Special-IV Limited Partnership v. Rickey Newsome, No. 16-0998

-

Anadarko Petroleum Corporation and Anadarko E&P Company, L.P. v. Houston Casualty Company, et al., No. 16-1013

-

Larry Eddington, Vincent J. Aurentz, and William J. Butler v. Dallas Police and Fire Pension System and William F. Quinn, in his official capacity as Board Chair, No. 17-0058

-

Compass Bank v. Francisco Calleja Ahedo, No. 17-0065

-

Exxon Mobil Corporation v. the Insurance Company of the State of Pennsylvania, No. 17-0200

-

Tracy Windrum, Individually, and on behalf of her minor children, B.W., J.W., and H.W. v. Victor Kareh, M.D., No. 17-0328

-

Hays Street Bridge Restoration Group v. City of San Antonio, No. 17-0423

-

Glassdoor, Inc., Doe 1, and Doe 2 v. Andra Group, LP, No. 17-0463

-

Eric D. Hillman v. Nueces County, Texas and Nueces County District Attorney’s Office, No. 17-0588

-

Rosenberg Development Corporation v. Imperial Performing Arts, Inc., No. 17-0660

One of the petition denials today involved a dispute over whether Texas’s public-information laws require state officials to reveal which pharmacy has been providing Texas’s execution drugs. The Austin-American Statesman has coverage: “Court upholds ruling requiring Texas to reveal execution drug source” (Jun. 1, 2018)

Tags: Order Lists · Practice Notes

May 30th, 2017 · Comments Off on Are the SCOTX dissents coming in June?

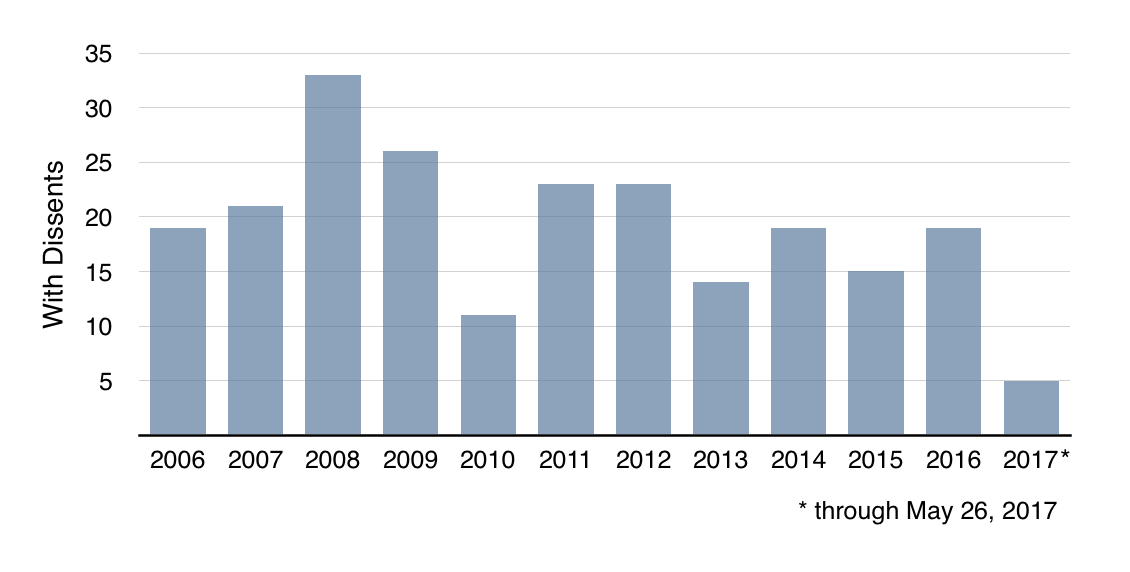

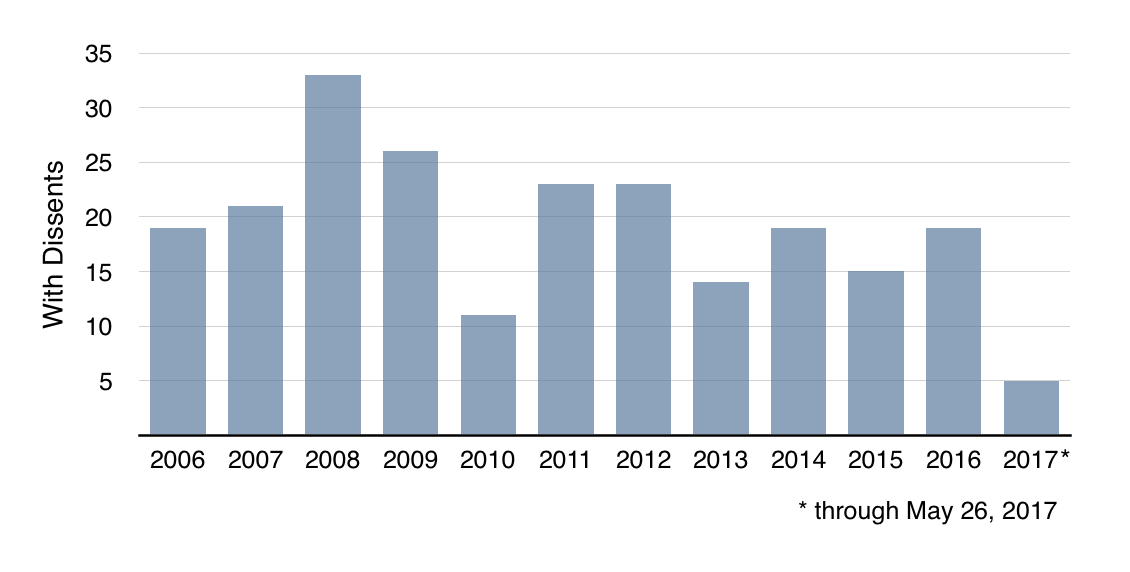

I’ve been publishing voting stats about the Texas Supreme Court since 2010, but my first project was a look back at four years in which the court had the same nine members (the 2006 to 2009 terms). Over that span, the court issued about 25 decisions with a dissent each year — and about 9 per year were 5-4 votes.

The 2010 term marked a recent low with only 11 cases receiving any dissent from the judgment. Since then, the totals have been 22, 23, 14, 19, 15, and (last year) 18 decisions with dissents. (You can poke through the details on the Texas Supreme Court voting patterns charts.)

With a month to go, the total for the 2017 term is only 5:

As it happens, dissents saw a similarly slow start last year. Through May 2016, the court had issued only 7 decisions with dissents — before a surge of dissents in June pushed the year-end total to 18.

Should we expect this term to be similar? Or will this be the fewest dissents since at least 2005?

If placing a bet, I would take the “under.”

The short reason why: there are very few “older” argued cases yet to be decided.

For obvious reasons, it takes longer to to produce decisions with dissents than without. Some time is needed for an internal back-and-forth of drafts among the justices. The dissent reacts to what the majority writes, and often the majority makes improvements and adds a section respodning to the dissent. In rare instances, a dissent might even persuade enough other justices to win the day. (If you see a published “dissent” with an unusually detailed fact section and procedural history, that might be a tell.)

Most of the dissents published in June 2016 were from cases that had been argued the previous fall (or even earlier), so the court had plenty of time for its internal deliberations. Only three of last June’s dissents were for cases argued that spring.

In 2017, those older cases are already off the board. Only a single case remains from last fall’s argument calendar (Pagayon v. ExxonMobil, No. 15-0642). Only two remain from this January. The other sixteen cases were argued in the February or March sittings.

Although I wouldn’t bet on a large number of additional dissents, it’s always possible. The cases argued late this spring might prove especially contentious. What’s clear, however, is that if the court does release a significant number of dissents this June, they will have been written in impressively short time.

Tags: Practice Notes

April 21st, 2014 · Comments Off on A look at voting patterns and amicus practice in the Texas Supreme Court

Earlier this month, I made a presentation with Justice Willett about recent voting trends on the Texas Supreme Court — with a few extra slides included about the state of amicus practice in the Court.

Here are the slides (PDF):

This was in some sense an update of the talk we made to the Austin Bar appellate section in 2010. Then, we had focused on the unique 2005-2009 Terms of the Court, during which there was no turnover of Justices. The new presentation looks at the voting patterns as the Court’s membership has changed from 2010 to the present — including some of the diagrams of voting patterns that were so popular before.

This time around, I also included two new kinds of graphs: (1) a look at how often each Justice tends to join in concurrences or dissents; and (2) a time-series showing how each Justice’s overall rate of agreement with the judgment moves year to year, and relative to similar peers.

The last section of the talk discussed amicus practice. The slides that seemed to make the biggest impression were the last handful, which show the correlation between response-request rates, briefing-request rates, and grant rates when at least one amicus brief is in the file.

Tags: Practice Notes

January 15th, 2014 · 1 Comment

I’ve been asked to pass along this happy news: Effective immediately, the Texas Supreme Court does not require any paper courtesy copies for e-filed documents.

That’s zero, none, zilch. No paper.

The only people sorry to hear this will be a few local print shops.

Tags: Practice Notes

September 12th, 2013 · Comments Off on A “statpack” about the Texas Supreme Court’s 2012-2013 term

I put together this deck with my statistics for the Texas Supreme Court’s latest term, which ended on August 31, 2013. The numbers are drawn from my own case-tracking database, so they are unofficial.

I’ve posted the slides on slideshare. For a full-screen display, look for the  button.

button.

Some of the slides show:

- the voting patterns of the Justices (including the newest additions, Justice Boyd and Justice Devine);

-

which Justices are aligned with or against the judgment most often;

-

with the Court’s new emphasis on prompt decisions, how long cases are taking to reach a decision after oral argument; and

-

how the time to decision for a case may vary with argument date, with the number of split opinions, or by authoring Justice.

As always, I appreciate any feedback and questions.

Tags: Practice Notes

June 18th, 2013 · Comments Off on “Putting the ‘App’ in Appellate Practice”

That was the title of a panel that I was asked to participate in last week at UT’s Conference on State and Federal Appeals here in Austin.

The other two panelists were Blake Hawthorne (the Clerk of the Supreme Court of Texas) and Rich Phillips (of Thompson & Knight). We spoke about some practical ways to use an iPad to get actual (and, yes, even billable) appellate work done.

Blake focused on ways to read and annotate PDFs, a topic of particular interest to judges adapting to Texas’s new e-filing system. Rich focused on ways to work with appellate records and do legal research. And I focused on how to use the iPad as part of the writing process.

Our presentation included live demonstrations and some video captures of using the iPad. The version below does not have either, but we have included a few screenshots to give you a flavor of what we discussed.

Find out more:

-

Download the full slidedeck.

-

Download the conference paper for this talk, which lists some of the apps we discussed.

Tags: Legal Tech · Practice Notes

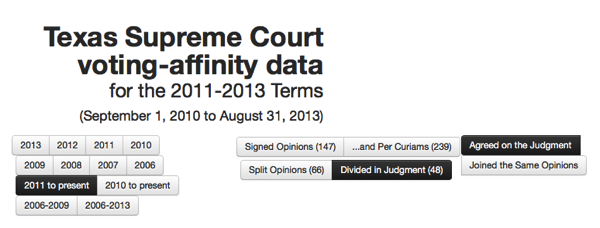

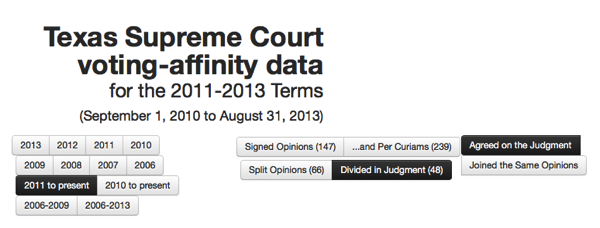

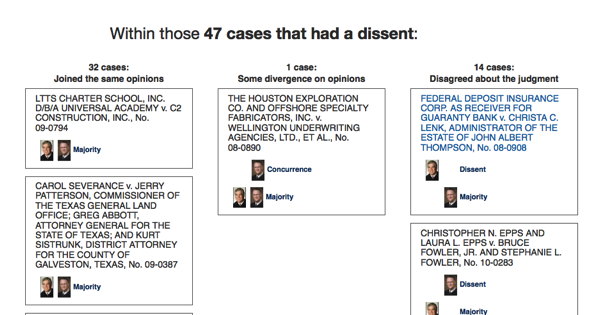

April 10th, 2013 · Comments Off on Texas Supreme Court voting statistics for the most recent terms

At popular request, I’ve published a new set of voting charts for the Texas Supreme Court. These charts are tied directly to my court-tracking database, so they can be kept current.

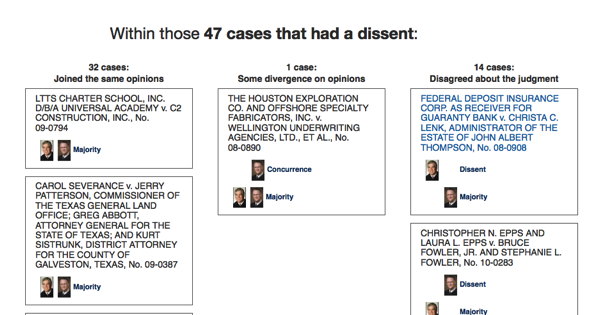

If you just want a general sense of the voting dynamic, then the top-level percentage totals are what you need. But as an advocate, I want to know which types of cases and legal arguments led two Justices to disagree. To accomplish that goal, my system allows you to drill down and see the specific opinions that led to each set of agreements and disagreements.

As a bonus, this also makes my math transparent. By clicking through, you can see exactly which cases were rolled up to compute each percentage in the chart (and, I hope, will let me know if you see any data points that need to be adjusted).

How often do the Justices vote together?

The basic voting chart shows how often the justices on the Texas Supreme Court vote together.

If you want to change the time period or focus of the chart, just pick one of the options at the top of the main page:

Those options show the pattern I look to most often: whether each pair of Justices agrees about the judgment in those cases where at least one Justice dissented.

Using that set of criteria, the pair of Justices with the closest voting record since September 2011 is Justice Johnson and Justice Wainwright at 84%. Focusing just on current Justices, (( The second- and third-closest pairs also involved Justices who have stepped down: the pair of Justice Wainwright and Justice Guzman was ranked second, and the pair of Justice Medina and Justice Lehrmann was in third. )) the closest pair is Justice Green and Justice Johnson at 70%.

Over the same time period, the pair of Justices who voted least often for the same judgment in divided cases was Justice Johnson and Justice Lehrmann, at 29%.

One of my favorite features of these charts is that you can click through to see a complete breakdown of how each individual pair of Justices voted — one a case-by-case basis:

From the detail pages, you can click on the words “Majority” or “Dissent” under each case to jump to the specific opinions about which they agreed or disagreed.

Who has written which opinions?

Each year, the OCA publishes a leaderboard of how many opinions each Justice has written, broken down by type of opinion.

I have a similar chart that shows the current count (through last week’s opinions): Texas Supreme Court opinions by Justice. You can click on the values in the chart to reach a backup page listing which specific opinions fall in each category. (( OCA does have one data set that outsiders don’t: knowing which per curiam opinions were penned by each Justice. For previous years, I have updated my chart to display the number of per curiam opinions that OCA has later reported were written by each Justice, but the backup pages don’t try to guess who wrote each of the per curiams. ))

So far, the 2013 Term has not been very contentious, with just 5 separate opinions in the partial term (just over seven months so far). By comparison, the full 2012 term had 26 separate opinions and the 2011 term had 45 separate opinions.

One factor, no doubt, is that the Court is still absorbing its two newest Justices. We’ll have to wait to see how the pattern plays out for the rest of the term. (These chart will continue to be updated as more opinions are released.)

Who has joined the opinions written by each Justice?

You can think of this third category of chart as a combination of the first two.

It shows how often each Justice joined the opinions written by each other Justice. Each row on the chart shows the opinions authored by a particular Justice. Reading across, you can see how many of the opinions were “solo” separate opinions and how many were joined by each of the other Justices with which they sat on that case.

Using the controls at the top of the chart, you can also narrow its focus just to dissents, just separate opinions (concurrences and dissents), or just deciding majority opinions.

Tags: Practice Notes