In November, the Austin Bar appellate section hosted a talk by Professor Schiess about legal writing. In a Q&A exchange, someone asked a provocative question: Are there empirical studies suggesting that better-written briefs produce better outcomes for clients?

So I was struck to see a headline come through my feed reader last week: “Does the Readability of Your Brief Affect Your Chance of Winning an Appeal?” (PDF).

The study used some generic ways to calculate “readability” — the Flesch Reading Ease scale the Flesch-Kincaid Grade-Level scale. (( If you want to point one of these at your own briefs, Microsoft Word will compute them after it completes a spell check.

And if you’re wondering, no, the study authors did not remove citations from the briefs. I’m sure that made the study far easier to do, but I’d be curious to know if they did a small sample test to see how it skewed the data. ))

The answer will be disappointing to legal writers (and doubtless to legal readers). The authors did not find the correlation they set out to find. Given that the measures they chose for “readability” just use factors such as sentence length and syllable count, they do not necessarily pick up the difference between a “good” and a “bad” brief. What’s missing might be better tools to distinguish the two.

But the study did have some other interesting findings:

- There was not a significant difference between state and federal appellate courts, except…

-

“United States Supreme Court petitioners, respondents, majority opinion writers, and dissenting opinion writers are all less readable on average than their lower-court counterparts.”

-

And “at the United States Supreme Court level, the Justices’ writing is significantly less readable than the lawyers’ writing.”

The stilted style of U.S. Supreme Court practice

Those preliminary findings about the U.S. Supreme Court ring true to me. The briefs read differently. It’s not the bound booklets or the famous Century Schoolbook type; it’s something about how advocates approach the writing. (( The researchers also showed some differences between majority and dissenting opinions. In the Supreme Court, contrary to what you might expect, dissents are less “readable” than majority opinions. They kindly did not provide a readability score for each Justice. ))

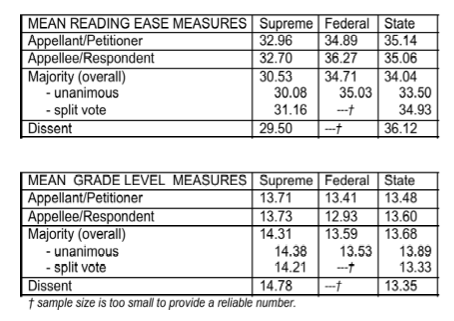

Here’s what the numbers showed. (In the top group of “reading ease” measures, higher is better.)

The simplest explanation of those numbers makes the most sense to me: Advocates strive to sound more formal in the Supreme Court, and the Justices more formal still. That effort drives down the readability of the briefs under these two measures.

How does your writing voice change to different courts?

What say the law professors?

They suggest on page 14 that “Supreme Court practitioners should try to be a little less readable…” to fit in with the culture of Supreme Court briefs.

Count me as a skeptic. If a more complex sentence structure is a byproduct of trying to make a good argument, so be it. But consciously setting out to add complexity seems… ill-advised.

So I decided to look in the mirror to see if my own writing changed. I had one easy set of data — a recent pair of amicus briefs that I wrote as a case moved forward, first to the Texas Supreme Court and then to the U.S. Supreme Court. Did my writing become less “readable” as a I rewrote the brief for a new audience?

By the study’s chosen readability measures, yes, my writing did get more complex. In my Texas amicus brief, the grade level was 11.3 and the reading-ease measure was 45.8. (( I was at first happy about those scores compared to the averages presented in the paper. Then I learned that “reading ease” is measured on a 100-point scale. This blog post, for example, has a score of 69. )) In my U.S. Supreme Court amicus brief, the grade level went up to 12.0 and the reading-ease measure declined all the way to 38.7. (According to Word, I also used about twice as many passive-voice sentences.)

That’s only one example, but it will give me something to think about the next time I’m adapting an argument for a new court.

Hat tip: Law Prof Blog

1 response so far ↓

1 Kendall // Feb 15, 2011 at 10:25 am

I have long thought that Supreme Court practitioners could not write a lithe and graceful sentence in the King’s English if their lives depended upon it. Indeed, I suspected as much of any lawyer east of the Mississippi river. This confirms it.