I’ve written before about how to use Google’s normal search index to find unpublished opinions in Texas.

Google has now formally added legal opinions to another of its products — Google Scholar — promising new ways to research legal case law (and some legal journals, too).

This is something that I have been expecting to see from Google for a few years. Google has clearly put the extra time to good use. Its first attempt is quite polished and looks like it might be usable for serious legal work.

And, in typical Google fashion, the price is right. (( Interestingly, they chose to integrate legal cases into Google Scholar, which lets academic publishers keep the full text of their articles behind a paywall. I will be curious to see if some legal treatises and reference books show up with those same paywalls attached. ))

The rest of this post is a quick walk-through of the service with some first impressions.

A quick sample search

To get started, click the “Advanced scholar search” link that’s wedged next to the main search box on the Google Scholar page. It should take you here.

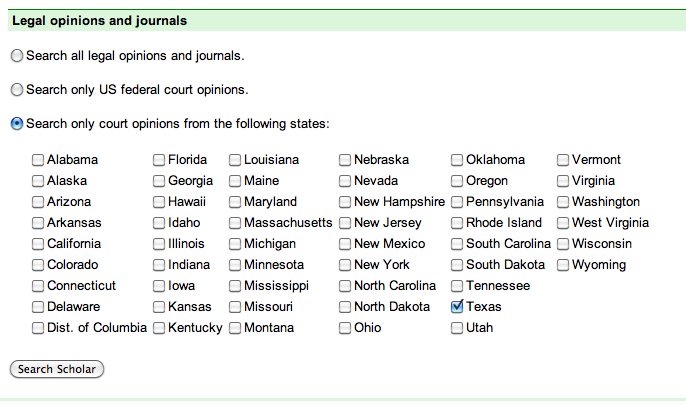

Scan down the page to the “Collections” option. From here, you can specify which legal sources you want to search.

For this demonstration, I’m going to search for “sovereign immunity” and “declaratory judgment” by putting those two phrases (in quotation marks) in the top search box on this page (the one labeled “with all of the words”).

Hit the “Search Scholar” button. (There’s one at the top right of the page and another at the bottom left.)

Smart results

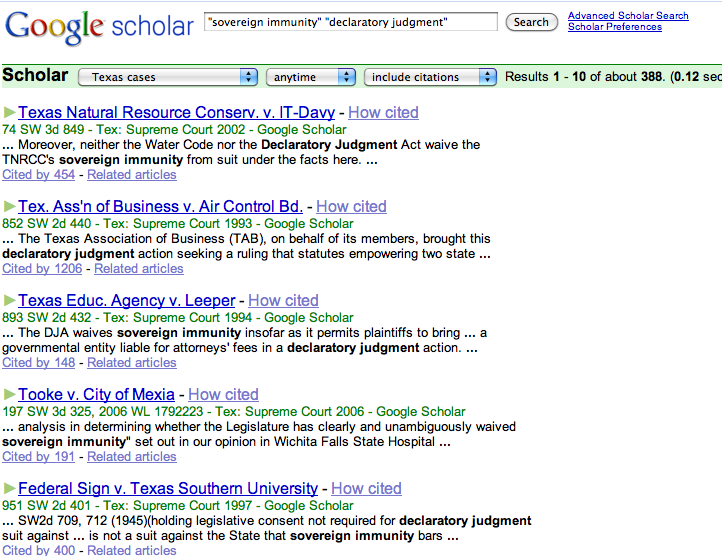

At first glance, that’s a pretty smart result set:

- It’s listing some of the most cited cases about those subjects first, although it’s clearly using other factors, too. (It shows the number of citations for each entry.)

-

Perhaps as a byproduct, it’s listing the state supreme court (the court with the most legal authority) first

-

It’s giving you an excerpt from the case with the keywords highlighted

-

In typical Google style, it has a couple of mysterious links taking you to related materials (the large “How cited” link next to the case name and the small “Related articles” link beneath the blurb.)

Looking closer

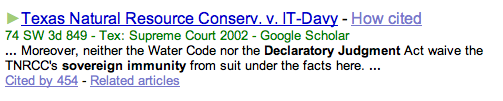

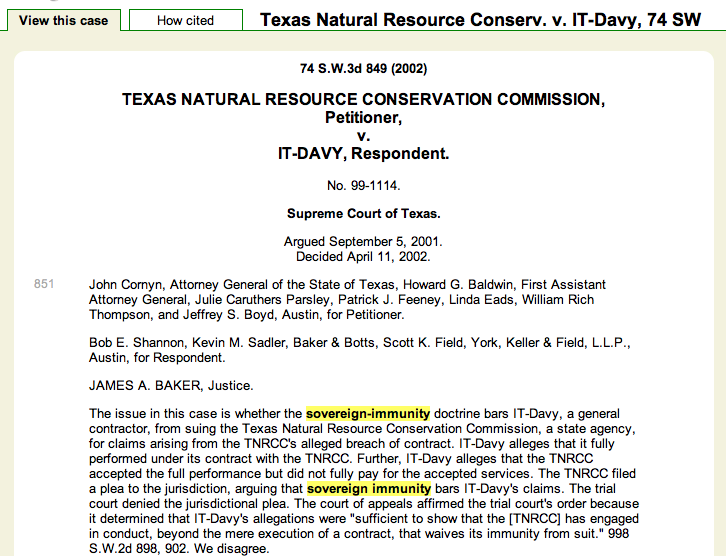

Let’s look at the first result in detail.

Click the case name, and it takes you to a nice representation of the case — with the West reporter page numbers listed on the left margin, so you can easily cite this in a brief. (( If you scroll down, you’ll notice that the IT-Davy case used in this example has three opinions (majority, concurrence, dissent). Google Scholar doesn’t yet have a nice way to navigate these, and I don’t yet know how smart its algorithms are about distinguishing this text in search results. ))

Search results are highlighted. Case citations are hyperlinked to their locations within Google Scholar.

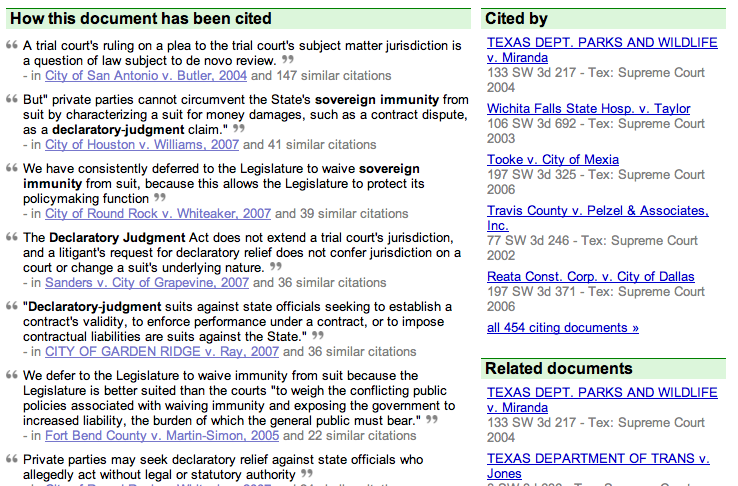

Want a citation tree? Go to “How Cited”

At the top there is a “How Cited” tab.

That takes you to Google’s take on a citation history. On the left, you can see snippets from the citing sources. (Interestingly, those snippets also highlight your original search terms so you can scan for possibly more related hits.)

If you click on an item in that list, you are taken directly to the relevant part of that citing case. Nice.

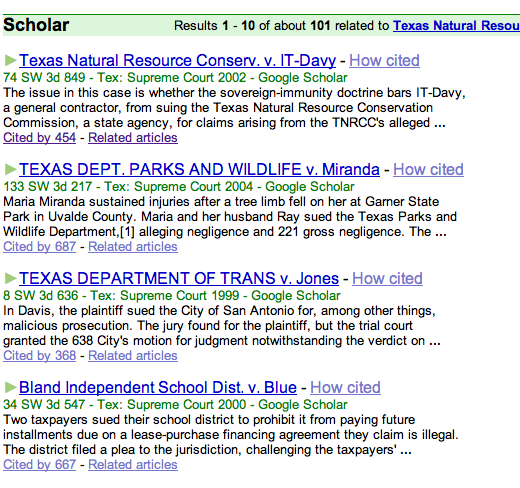

A first look at the mysterious “Related articles” link

The “Related articles” link is more mysterious to a legal scholar. Clicking it brings up a more spartan list of authorities than the “How cited” tab.

It’s not a citation tree — the number of results is smaller. It lists the case you’re starting with as the first result, and the results contain both older and newer cases. At first glance, it looks much more like a “Genius Playlist” in iTunes than a citation tree. (( I don’t know how Google is calculating this. (Perhaps someone more familiar with Google Scholar’s academic offerings can comment.) ))

What’s immediately striking is how the blurbs beneath each entry on the “Related articles” page differ from the “How cited” page.

Rather than trying to give you the most “relevant” text, the blurbs on the the “Related articles” blurb are sometimes (but not always) the very beginning of the opinions. My guess is that Google has an algorithm that is trying to give you a sense of the subject matter of the listed case. The results that algorithm is generating still look pretty primitive, at least for legal results. But it’s an interesting idea.

If someone has more insight into this “Related articles” feature, please let me know.

I’m giving it a real-world tryout, and I’ll report back

With perhaps an abundance of optimism, I’ve decided to try out Google Scholar on some of my current briefs. I will report back.

I already see nice ways to limit search results by year. I don’t yet see a logical way to search for opinions just from a particular court of appeals, which is an important feature for Texas appellate lawyers. (Knowing Google, there is a search parameter that will accomplish this.)

I’ll also pass along some more tips when I have some hands-on experience.

More reading [added 11/18/2009]

Because of the strong response to this post, I wanted to offer a few more links for those of you who were interested enough to read to the end.

-

The horse’s mouth: “U.S. Caselaw in Google Scholar” by Rick Klau, who was on the Google team that built this service. If you like the service, let him know.

-

This post by Professor Eugene Volokh praising the new service, but noting some of its early blemishes (including some strange metadata glitches).

-

This post on Internet for Lawyers has some updated information about the scope of caselaw that is included in this first iteration.

-

And here are some first reactions from Thomson West and Reuters (from Common Scold).

10 responses so far ↓

1 Mike // Nov 17, 2009 at 12:14 pm

So is there a way to use Google for statutes and administrative stuff? As a law student I have access to those things now, but Google seems much more capable of creating a user-friendly search algorithm. I think I hate Westlaw and Lexis. They are just far too formulaic to be used quickly, especially when starting out. If a search engine requires that I learn a bunch of rules and methods before doing a basic search, I consider that a fault of the search engine. I want a search that does my job for me, dad gum it!

2 Lily // Nov 17, 2009 at 9:23 pm

Looks like there are no pages within opinions, so it would be impossible to do pin cites (unless I’m missing something).

3 Don Cruse // Nov 17, 2009 at 9:44 pm

Lily:

The cases I have worked with show a page number in the left-hand margin corresponding to the reporter page breaks.

I’m told that this is very close to accurate — there might be times where it’s off by a few words. If your quote starts or stops exactly on that line, you might need more precision.

Are you seeing something different on the cases you’ve looked at?

4 Don Cruse // Nov 17, 2009 at 9:47 pm

Mike:

No, this tool isn’t smart about statutory citations (at least not yet). The statutes and rules are not hyperlinked. Also, the search box doesn’t yet know that “Tex. R. Civ. P.” is the same as “Texas Rule of Civil Procedure.”

At least in Texas, there are good ways to get the text of statutes and (most) rules online from the horse’s mouth, so to speak. I tend to go directly to the Legislature’s website to find statutory language. Their format is not perfect, but it’s easier for me to work with than the way the paid publishers dice up the statutes.

5 Lauren // Nov 18, 2009 at 1:59 pm

Thanks for this, I’ve already started using it based on your review/instructions. One small issue that I’ve seen is that the left-hand margin pin cites don’t show up when I print. I can see them on the screen but not on my print-out. Also the first line on each page after the first page is cut off. Any printing tips?

6 Don Cruse // Nov 19, 2009 at 3:13 pm

Lauren:

I had a chance to try out printing today. I tried three browsers: Firefox 3.5, Internet Explorer 7, and Safari 4. Two of them worked pretty well. The third… didn’t.

The browser that didn’t work for me was Firefox. I couldn’t see any page numbers after the first printed page, although they were fine on the screen. I’m not quite sure why Firefox’s printing engine messed this up — the page numbers seem to be using pretty standard web formatting (CSS) behind the scenes.

Google could fix this by having a “print” button that returned a PDF or something pre-formatted. Or I suppose someone could come up with a Firefox plugin to try to do the work. In the meantime, this is bad news for Firefox users who like to print their cases out onto paper.

7 Randy Becker // Nov 20, 2009 at 3:00 pm

The page numbers in the margin are highly accurate. They actually occur somewhere specific within the line on which they are shown. The only places that I have found them to be different from a physical reporter is where a page break occurs within a word, in which case Google will place the break after the word.

I’ve written an extension for Google Chrome that displays them inline, as star pagination. If you’re using Chrome, and have enabled extensions, you can use mine to display page numbers inline – http://links.lawstoreapp.com/stars

8 Don Cruse // Nov 20, 2009 at 3:09 pm

After I did some poking around, I saw how Google was marking those page breaks within the text and thought that a plugin like you’re describing would be a great help. Thanks for writing one and posting the link.

As a Mac user, I’d like to see a similar tool for Firefox — or see Google finally release their Mac version of Chrome.

9 Lily // Nov 24, 2009 at 10:12 pm

The plugin is great — thanks!!

10 Charlie Campbell // Feb 15, 2010 at 2:26 pm

Don:

Great write up, I too was ecstatic the day the legal portion of Google Scholar went live, but my excitement waned to some degree as I learned its limitations. Its a great “natural language” type of search system, much better in my opinion than Westlaw’s, but it lacks the precision that Westlaw’s “terms and connectors” search has.

I rely on the boolean type search of Westlaw to sift through the abundant caselaw out there to find what I am looking for. I can greatly cut down on the amount of time I spend finding cases if I precisely pick my terms. However, the boolean operators and limiters of Google Scholar, especially the legal portion, are sadly limited, greatly reducing its utility to me. Yes, I can find cases with it, but it generally is slower because of the abundance of cases that come up that aren’t on point.

That said, I love the speed of Google’s servers, blindingly fast in comparison to West’s snails. Westlaw continues to raise prices, but their servers are slow as ever. Furthermore, the citation system Google employs is great. Much more intuitive than West’s in my opinion, and very useful. Not perfect, for it lacks the positive/negative treatment categorization, and the degree of discussion, but the snippet of how the case was cited is nice.

In short, I think West and Lexis certainly have something to worry about, but Google still has some work to do. If you’re listening Google, improve your boolean connectors and limiters, and don’t force me to use your cool stemming technology; sometimes when I search for “behavior” I don’t want to be returned results including “behave.”